“Too high a price is asked for harmony; it’s beyond our means to pay so much to enter on it.” – Fedor Dostoevski, The Brothers Karamazov (1880)

Contrary to what Dostoevski wrote, communication between people can be harmonious, even downright civil, even though emotions are high and differing viewpoints struggle to prevail. Nor is the price too high. The principle underlying this harmony is straight talk, and the key is the eleven ground rules.

As you read about each rule, you’ll learn how these rules can lead to communication that is both heated and productive. There is no need to distinguish between a conversation filled with passion and one filled with trust.

First, here are the eleven ground rules again:

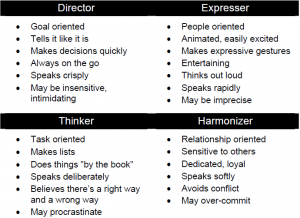

The first ground rule is to review each other’s style of communication. There are two parts to this rule:

The first ground rule is to review each other’s style of communication. There are two parts to this rule:

Talking about styles of communication is an excellent ice-breaker.

Tip: The Team Profile comes with an individual print-out for each member.

This rule applies to all conversations and all situations. Think about how easily conversations can get off track because of loaded terms and labels. Take a phrase like “maximizing productivity” or “thinking strategically.” What is, after all, “productivity?” What is “strategic thinking?” Some of the best minds have difficulty defining these terms; it’s no wonder that organizations stumble over them.

There are no shortcuts to defining key terms. The purpose of this ground rule is to give people the freedom to challenge words and phrases that seem unclear. Whenever this happens, the conversation should be placed “on pause” until everyone agrees on the definition – or agrees that the word or phrase is too loaded to be used at all. Remember, you can’t have straight talk until you agree on what words mean.

This rule seems obvious. Unfortunately, it’s easy to say, hard to do. Much of our behavior is defensive. If someone challenges our views, it is ingrained in us to respond defensively, to challenge the other person’s ability to see things clearly. In so doing, we shift the focus from the issue to the person – and in so doing tread over this ground rule.

Ken Macher, one of my colleagues, distills the essence of this ground rule into an epigram: “Value learning over your own defending.” If you remember that competence in communication is being open to other points of view, that it’s assuming your own viewpoint is inherently limited, that it’s displaying genuine curiosity about other people’s viewpoints, you’ll never get in trouble.

The goal of straight talk is to increase understanding among all participants. Side conversations are clearly aimed at something else. Side conversations are distracting; they divide the group’s attention; and more often than not, they are a sign of disrespect for the process.

If you are genuinely committed to straight talk, your attention should be 100 percent focused on a single conversation, tracking both its content and its quality. Participants in a discussion need to be scrupulous in policing against side conversations. “Could we have one speaker at a time?” is a good, gentle reminder when people are in violation of this rule.

The value of this ground rule is twofold: First, it forces people to recognize that some of their best and most honest communication occurs outside the room, where only friendly eyes and allies are listening. This may be a more comfortable setting, but it’s not going to increase understanding. It is obligatory, given the goal of straight talk, to bring these conversations into the room.

Second, this rule enables people to admit that certain topics are difficult. It enables people to introduce an issue by saying: “This is a back room conversation that I’m bringing up here, because we’ve agreed to do so. I’m not comfortable doing so, but here goes….” This lets people see the context of the discussion and opens the door to a constructive line of inquiry.

Of all the ground rules, this sixth one is the most easily violated. What is enough focus? Can’t a tangential discussion actually be productive? This ground rule is dependent on making sure that everyone understands three things:

The beauty of this process is that it enables everyone to track the logical thread of the discussion, even while its focus shifts. People should be able to mark the end of one discussion, and the beginning of another. So long as everyone in the room understands this dynamic process, and can communicate to each other how the current topic relates to the original question and to the desired destination, then the focus is maintained. Everyone is playing by the rules.

Explain the reasoning leading to your conclusions. This seemingly simple rule is the most important element of straight talk. Adhering to it leads to straight talk. Departing from it can cause communications to break down in a hurry.

The tendency to accept our conclusions on their face – to not challenge our reasoning – is one of the root causes of miscommunication. Because we don’t challenge the way we think, we don’t develop the muscles that allow us to have productive dialogues. Instead, we engage in a kind of circular logic in which we make an assumption – and then draw a conclusion based on it.

The next tool is directly related to the Circle of Assumptions: Invite inquiry into your views. The purpose of this tool is to help push ourselves closer toward the center of the circle, toward the data. It lets people know we’re open to letting our reasoning be tested and probed. It says, in essence, “I might not see this clearly. I realize there are other ways of looking at it. Can you help me?” you set the stage for effective communication.

Straight talk occurs when people invite inquiry. A genuine display of curiosity creates an environment of constructive communication. It enables people to examine your assumptions. It causes them to look at their own. In so doing, it leads the group toward agreements about data, away from assumptions.

There’s an obvious synergy between these last two rules. People respond to the behavior of those around them. The more you inquire into your own views, the more you encourage other people to feel comfortable when someone probes their assumptions.

How you frame this challenge is vitally important. “How in the world did you reach that conclusion?” isn’t genuine inquiry. Translated, it really says: “You dummy, how could you possibly think that?” Under the rules of straight talk, your inquiry must be framed positively. “I know I’m not capable of seeing everything. I’m interested in understanding your perspective more fully. Can you explain your reasoning?” If you find the process frustrating, ask for help. “What am I missing here? Can someone help me understand it?” That allows the conversation to shift from you to someone else. And meanwhile, the ground rule remains intact.

The tenth ground rule encapsulates one of our tools – Inner Scripts. Getting people to divulge their Inner Scripts gets them pointed toward straight talk. This is one rule that everyone must adhere to – or no one will.

Most important, recognize the assumptions hidden in your undiscussibles. You assume that by raising a delicate issue people will feel upset. But maybe not. If you test your assumption by bringing it into the open, you’re likely to find that people feel relieved to have a chance to talk about it. The resulting discussion may break a logjam that’s been preventing the group from a successful dialogue.

One of the most important tools of straight talk is the Chain of Missing Data because it enables people to reach an agreement. The eleventh ground rule captures the essence of this tool.

It helps to analyze the data missing from a conversation. The starting point is to flag all assumptions. Next, identify the data needed – and possible sources for it. Notice how many assumptions can be resolved using the same data – or the same sources of data. Once you’ve flagged the missing data, prioritize which data is most important.

This post laid out the eleven ground rules in detail. Each rule works in conjunction with the others. Together, they orient a group’s communication toward shared learning and understanding of complex issues.

These ground rules need not be used in all meetings or communications. But the more they are built into an organization’s culture, the more that culture will shift from defending to learning – and the more capable it will be of marshaling its collective knowledge into a powerful strategy.

Download the PDF – Ground Rules for Productive Meetings Related Post – When Ground Rules Aren’t Enough

Leading Resources, Inc. is a Sacramento Consulting firm that develops leaders and leading organizations. Subscribe to our leadership development newsletter to download the PDF – “The 6 Trust-Building Habits of Leaders” to learn more about how to build trust with your team.

4 Replies to “The Eleven Ground Rules List”

Comments are closed.