Each communication style tries to manage conflict in different ways. The following chart shows how each style approaches conflict and responds to it, both in positive and negative ways.

Each communication style has certain “triggers” that spark them to react in negative ways.

| Directors are triggered by the perception that the span of their authority has been reduced. | For Expressers, it’s feeling that their ideas aren’t valued. |

| For Thinkers, it’s thinking that procedures aren’t followed. | For Harmonizers, it’s thinking that other people’s feelings aren’t considered. |

These triggers are style specific.

These triggers are style specific.Questions of authority, for example, will not “trigger” a Thinker. Likewise, sensing that too little attention has been paid to other people’s feelings won’t “trigger” a Director.

Sensing that a Director hasn’t participated fully in the discussion, you would ask him directly whether there are questions he’d like to raise. Sensing that a Harmonizer has tuned out of the conversation, you would ask whether there are any concerns about how the group is working together – and look in the Harmonizer’s direction.

In instances where conflict arises, you have three strategies to choose from. Choosing your strategy depends on how you read the room.

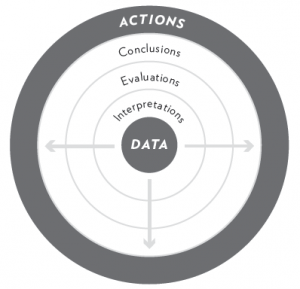

The initial, and correct, response when a conflict occurs in a group is to listen, acknowledge the various points of view, and then inject inquiry to bring the conversation back toward the center of the Circle of Assumptions, back toward the data.

The initial, and correct, response when a conflict occurs in a group is to listen, acknowledge the various points of view, and then inject inquiry to bring the conversation back toward the center of the Circle of Assumptions, back toward the data.

At the same time, make sure people are focused on the same purpose. Is the goal of the conversation clear? Are other agenda items getting in the way? If so, inquire whether there are any undiscussibles.

If the pattern continues, consider talking to the people involved outside the room during a break. Ask them whether they have any issues that prevent them from participating in the conversation in a constructive manner.

If the conflict surfaces again, your second option is to use the conflict to highlight the opposing points of view. You can say something like: “I notice that Dick and Sylvia are arguing with each other about this topic. Has anyone been influenced by their arguments? If not, why not?”

Then lead the conversation to a discussion of the issue, using Dick and Sylvia’s competing perspectives to push for a richer appreciation of the underlying data missing from the conversation. This has a second purpose, too: To help Dick and Sylvia become aware of their pattern, and avoid it in the future.

Then lead the conversation to a discussion of the issue, using Dick and Sylvia’s competing perspectives to push for a richer appreciation of the underlying data missing from the conversation. This has a second purpose, too: To help Dick and Sylvia become aware of their pattern, and avoid it in the future.

It poses few risks, but it does put people on the spot. You’ll have to decide whether Dick and Jane can handle the implied criticism, and also whether the group trusts you to be acting in their best interests. Assuming both things are true, “identifying” is a useful tool. If the same pattern continues, however, don’t use the group’s time to discuss it again. Take Dick and Sylvia aside and find out what’s going on.

A more risky intervention, but one that is warranted when a group gets bogged down by a recurring conflict, is for someone to focus on the dynamics of the conflict so it can be discussed directly.

For example, if two people seem to be replaying the same dispute again and again, to the detriment of the group’s progress toward a goal, someone needs to say: “I notice that Dick and Sylvia are having the same conversation again and again, and they’re disrupting the flow of our conversation. Why do you think this is happening?”

For example, if two people seem to be replaying the same dispute again and again, to the detriment of the group’s progress toward a goal, someone needs to say: “I notice that Dick and Sylvia are having the same conversation again and again, and they’re disrupting the flow of our conversation. Why do you think this is happening?”

Now you’ve shifted the focus to their behavior and have asked for feedback on its causes. Typically, you’ll get few responses at first. Then, after listening to the silence, you can pose the question another way: “What information could be useful to Dick or Sylvia in this situation?” This framing of the question will likely generate several comments.

Then, depending on the mood of the group, you can pursue one of two options: 1) move the conversation back to its original focus, having allowed the group to give feedback to Dick and Sylvia; or 2) ask Dick and Sylvia to discuss openly the reasons for their behavior, and then invite comment from the rest of the participants.

Basically, you’re putting the conversation “on pause” while you focus on personal feelings. People need to feel that they can be open about their feelings, and that requires a certain chemistry in the room. One should thoroughly understand the dynamics of the group before “focusing.” Even then, you’ve got to be prepared for someone to say: “I’m not comfortable talking about this.”

In which case, having opened the door, you could respond with: “Can you tell us why?”

Here’s a transcript from the dialogue that took place after “focusing” on the conflict between Dick and Sylvia:

Dick: I’m continually bothered by Sylvia’s way of assuming that she knows what’s best for us. She seems to think she can invent a new way of selling our products, and that the rest of us will defer to her. Frankly, I’ve got a lot more experience than she does, and she doesn’t appear to respect that.

Dick: I’m continually bothered by Sylvia’s way of assuming that she knows what’s best for us. She seems to think she can invent a new way of selling our products, and that the rest of us will defer to her. Frankly, I’ve got a lot more experience than she does, and she doesn’t appear to respect that.

Sylvia: Well, I’m bothered by Dick’s way of assuming that he knows best. He’s constantly reminding us to do it by the book, when there’s no book – at least in this case. Frankly, our creativity is what keeps us competitive. I think his approach is fundamentally flawed.

Spokesman for the group: So Dick, you think Sylvia takes too many risks, while Sylvia, you think Dick is too cautious. Is that right? What do other people think?

(Note that the spokesman has resisted the urge to draw the obvious conclusion: That Sylvia and Dick are experiencing a conflict in style. He’s instead recognized that his role is to encourage other people to talk.)

Babs (a subordinate): I see Sylvia and Dick as rivals for the direction of this company. They both want to lead it. And they’re both natural leaders. However, for now anyway, Dick is the leader. So Sylvia should ultimately give way.

Meg (another subordinate): I don’t see it that way. Sylvia doesn’t need to defer. But she does need to make her arguments in a more reasoned way. I’d like to see them ask each other more questions. I’d like them to explain their reasoning. No offense, Sylvia. (Laughter in the room.)

Babs: Yes, what Meg says is true, and I’d also like to see them give credit where credit’s due. Too often, Dick and Sylvia are warring with each other, so we don’t get a sense that they respect each other – or even like each other. That puts all of us on edge, because they’re such strong personalities. I never know whether this is a friendly joust or duel to the death. I’d like them to back off for a while, and appreciate each other’s contributions.

Spokesman: How do you think they could do that?

Babs: Well, Sylvia could say things like: “Dick’s approach is sound and is perhaps the way we should go on this.” And Dick could say: “Sylvia has once again shown a flash of creative genius.” That’s what I’m talking about. Appreciation. Acknowledging their unique talents.

Spokesman: Does everyone agree with what she said?

Dick: Sounds good to me.

Sylvia: Me, too. I think Dick and I forget to acknowledge each other’s contributions, especially in front of others. While we may be okay with our fights, other people may not be and it may make them feel very uncomfortable. That’s not smart. So we should recognize the cause of the discomfort is us.

Spokesman: Okay. So we’ve defined the problem, at least in part, and defined a solution. Do you want to keep talking about it some more, or shall we go back to the topic?

Dick: I think this has been very valuable. I’m glad to get the feedback.

Sylvia: I agree. I want people to know that I don’t want Dick’s job. He’s the leader. He’s invaluable in that role. And if I’m the fly in his ointment, well, then, I’ll try to make myself a bit sweeter. (Laughter)

Spokesman: Okay. So we’ll go back to the topic? Is this what the group wants?

Babs: I think we’d like them to back off each other a bit, but not from the conversation. That’s the distinction in my mind.

This transcript is a good example of the benefits of “focusing.” The sources of the conflict get clarified (in this case, the fact that Dick and Sylvia had erroneously assumed that other people were comfortable with them airing their conflicts in public); the parties involved tend to appreciate the chance to give feedback; and the conversation can proceed with heightened energy and enthusiasm.

But not always. Once, we were taking part in a conversation in which one manager, named Glen, kept saying that regardless of what decisions were made at the meeting, he alone was in charge of running his department. We stopped the discussion to focus on his defensive reaction. After ten minutes of talking, Glen got up, said “excuse me, but I have things to do,” and left the room.

We took a break, half expecting Glen to be outside the room waiting. But he wasn’t. Ten minutes later, no Glen. A half hour later, still no Glen. People were anxious about his whereabouts, so we adjourned in order for people check up on him.

But Glen had not gone back to the office. Nor, apparently, had he gone home, since calls there were unanswered. Someone decided to notify the police.

That evening, we heard from one of Glen’s colleagues. Glen had gone driving. He said he needed time to think. Later, Glen told us it was the best thing that happened to him in 20 years. He said it made him see how people perceived him. It was the same way he perceived his own father. And he vowed to break the pattern.

Moral of the story: Focusing on negative behaviors to resolve a conflict is difficult and risky. But it can be rewarding for all.

| Lesson 13: The Circle of Assumptions | Lesson 15: The Habits of Highly Effective Facilitators |

6 Replies to “How Each Style Manages Conflict”

Comments are closed.