A colleague of mine passed along an article recently titled, “History and Organizational Change.” Written by two scholars in Canada, Roy Suddab and William M. Foster, their argument is that the way we view history has a significant impact on whether we view ourselves as agents of change.

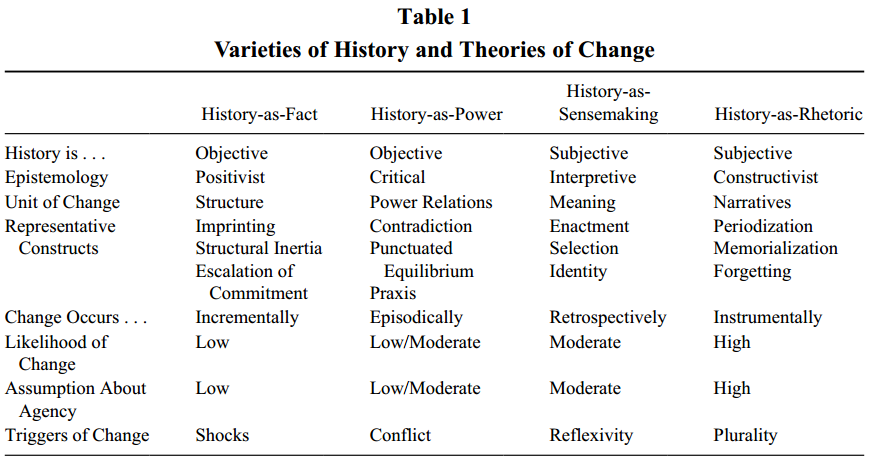

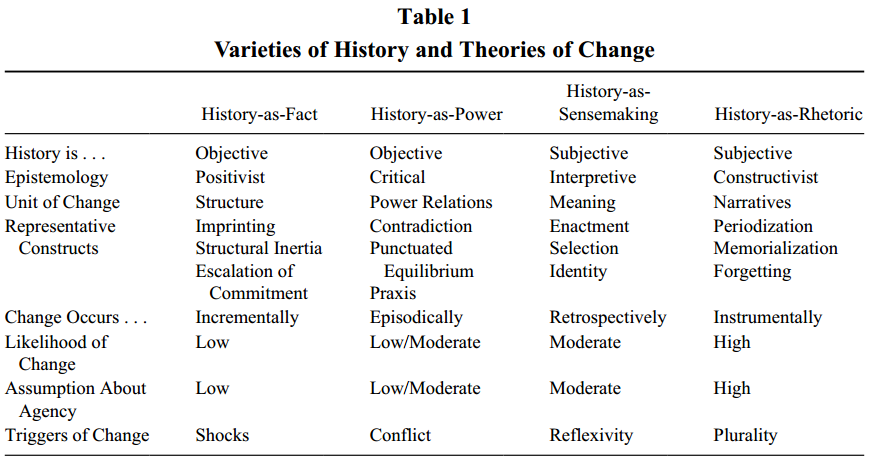

The authors present four different ways of viewing history.

The first, “history as facts,” views history as a set of essential facts that are unchangeable. This vision of history causes people to see themselves as constrained by history. When change does occur, it occurs typically because outside events force the change to occur.

The second, “history as power,” views history as a set of changing power relationships. In this construct, history is a set of forces that result in continuous change in power and power structures. At one moment, a given leadership team or political coalition may be ascendant, but ultimately it will give way to another group.

The third view, “history as sense-making,” views history as interpretations of the past. In contrast to first two models, here change manifests as a shift in meaning that occurs within a social group. Individuals and groups lay the groundwork for change by discussing their interpretations of history and deciding what those interpretations mean for the future.

The fourth view, “history as rhetoric,” argues that history is highly malleable and open to revision. People who hold this view see themselves as using their own specific narratives to shape history. In contrast to those who view history as occurring outside of oneself and constraining one’s action, this view bestows tremendous “agency” on individuals and sees them as facilitating strategic change through creative narrative shaping.

One implication of this article is that differences in our assumptions about history influence our ability to conceive of and manage change. Those who see the past as largely fixed and immutable are more likely to see an organization as similarly fixed and immutable. By contrast, interpretive assumptions about the past make organizational change more possible. The authors offer several interesting examples of how this has played out in organizations ranging from the Catholic Church to the U.S. Postal Service. As the authors point out, research in organizational storytelling has demonstrated that effective stories are far more persuasive or effective in changing attitudes than the use of statistics or other quantitative data.

For people who wish to lead and manage change, the article suggests that our assumptions about the nature of history determine our ability to shape effective narratives about the future of our organizations. It also highlights how a clash in perspectives among leaders may also impede change.

LRI’s consulting is designed to achieve real, meaningful change for our clients.

Client Member Area

Client Member Area