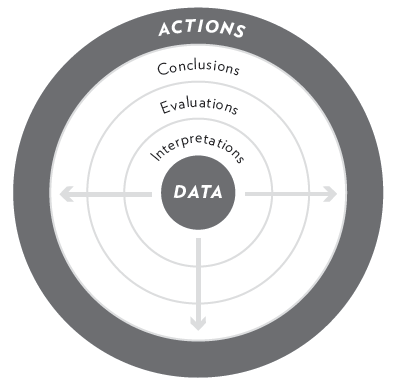

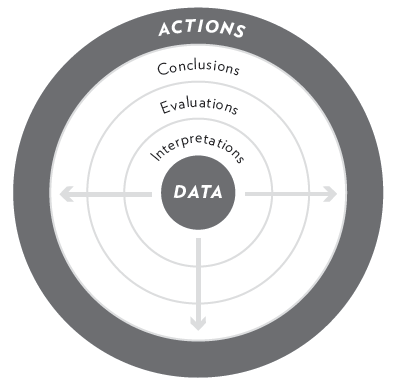

When discussing an issue or solving a problem, people often jump to conclusions before they spend time talking about what the problem is – or what data they have at hand. The Circle of Assumptions teaches us an orderly way to think about problems, starting with data and building toward conclusions. It enables us to see how easily our communication can be garbled by our failure to be aware of our own assumptions – and how they affect the conclusions we reach.

Here’s an example of a typical assumption at work:

Your boss is leading a discussion of the launch of a new software product in 12 weeks. He’s laying out the production schedule. A co-worker says, “If the launch is in 12 weeks, then we’re already two weeks behind schedule.”

Your boss is leading a discussion of the launch of a new software product in 12 weeks. He’s laying out the production schedule. A co-worker says, “If the launch is in 12 weeks, then we’re already two weeks behind schedule.”

Immediately, your mind draws the following conclusions:

- “Once again we’re behind schedule. Why do we always make this mistake?”

- “This is my boss’s fault. He should have seen this coming. I’m not going to take part in a project that’s bound to fail.”

At that moment, your boss pulls out a project schedule and says: “It’s funny. I anticipated your question. And if you look at our schedule, you’ll see we’re exactly where we planned to be. Because of our new supplier, we can get the product in the stores in less than eight weeks. We’re actually one week ahead of schedule.”

As your co-worker turns red, you thank your lucky stars that you kept your assumptions to yourself!

Clarifying People’s Assumptions

Psychologists know that people’s beliefs affect how they interpret data. So the Circle of Assumptions teaches us that people can get caught in self-justifying feedback loops, where they become blind to data which does not reinforce their beliefs.

A critical element of productive conversation is the ability to assess what people really know, and what they think they know. The Circle of Assumptions teaches us to drive back toward the center, toward the data, and to keep checking each other’s assumptions. People need to ask:

- “What are your assumptions?”

- “What assumptions do you think we are (or I am) making?”

- “What’s the data for that?”

- “What am I (are we) missing here?”

Skillful communicators frequently probe their own assumptions and challenge them. This sets the stage for other people to do the same. When people focus on the data that they’re missing, it allows them to move forward to resolve the problem rather than remaining mired in their assumptions.

- “Here are the assumptions I’m making. Please feel free to challenge them.”

- “I want to make sure we’re thinking clearly here. What data could we be missing? What assumptions are we making?”

- “I’m concerned that we may be assuming too much. Let’s start with what we actually know.”

- “What data, if we had it in our hands right now, would change our thinking about this issue?”

The Assumption of Competence

Adding a further layer of complexity is the fact that our brains are hard-wired with what psychologists call “the assumption of competence.” In essence, we perceive ourselves – and want to be perceived by others – as competent and infallible, not prone to error.

The assumption of competence is a well-known psychological syndrome that boosts our image of ourselves as competent and in control. It is thought that it played an ancient role in our survival by helping early human beings feel in control – despite overwhelming odds. Today, it drives much of how we behave. For example, it can result in self-justifying feedback loops, where people become anchored in their position, blind to data that does not reinforce their conclusions.

We unconsciously tend to assume we know more than we do, or that we have more power than we do.

The Assumption of Competence affects all of our communication and decision-making. Consider the following types of activities.

- A management team is examining strategic options. The CEO says, “It all boils down to the marketplace. If our competitor cuts his prices $1, then we’ll do the same. It’s as simple as that.” (In this case, the assumption of competence is that the CEO has the ability to respond to any price change. A second assumption is that pricing is the most important market driver, and that pricing flexibility is thus the only scenario to examine.)

- A manager is giving an employee her annual review, “I know you want a higher-paying position with our company, but we don’t have any openings now.” (In this case, the assumption of competence is that it’s good management to limit the conversation to an assessment of the situation, rather than explore the employee’s aspirations and discuss what the company can do to help her realize them.)

- A group of people is developing options for a new product. The team leader says, “We’ve got the best minds we need in the room, right here. Let’s hear your best ideas. From there, we’ll develop a plan.” (In this case, the leader extends his assumption of competence to include everyone in the group. In an effort to make everyone feel valued, he loses an opportunity to begin by saying: “We want to get all the possibilities are on the table. Who else should we canvass before we start narrowing our options?”)

To communicate productively, a group has to be able to challenge its members’ assumptions. The most important assumptions to examine are always the ones that people cling to most dearly. Often these assumptions are based on deeply held beliefs. Challenging these beliefs and assumptions in a productive way helps us learn and understand what motivates us – and can dramatically increase the quality of the group discussion and decision-making.

Dealing With Assumptions of Competence

Assumptions of competence can be sensitive to untangle. Consider this dialogue, in which Rachel is the manager.

Linda: “Our competitor bought this phone system. We’ve got to have it.”

Jack: “I’ve got 20 years experience. Believe me, we don’t need this system.”

Rachel: “What is it with you two? If you don’t stop fighting, we’re never going to get anywhere.”

Rachel wants the two of them to reach an agreement, but her communication is unskilled. Here’s another way to handle it.

Linda: “Our competitor bought this phone system. We’ve got to have it.”

Jack: “I’ve got 20 years experience. Believe me, we don’t need this system.”

Rachel: “Let’s examine the assumptions that we’re dealing with here. First, Linda, how do you think this phone system will benefit us?”

Linda: “Well, I think our customers are going to expect us to deliver the same level of service as our competitor.”

Rachel: “So your argument is based on that assumption, right?”

Linda: “Well, yes.”

Rachel: “Since this is an important decision, what additional information could we get that would help us clarify whether your assumption is correct?”

Linda: “We could talk to some customers, I suppose.”

Rachel: “Excellent idea.”

Jack: “Hey, let me interject something here. We don’t need this system because it’s too complex for our sales people to learn.”

Rachel: “That’s also based on an assumption, isn’t it?”

Jack: “Yes, but trust me, I’ve seen these people working with technology. There’s too much turnover to train them how to use a complex system.”

Rachel: “Aren’t you assuming it’s a more complex system to use? Perhaps we should test that assumption by talking to them, first.”

Jack: “I’m not going to waste my time doing that.”

Rachel: “So it’s your feeling that you already know what they’re going to tell you? Would you be willing to stake your job on that?”

Jack: “I didn’t realize it was so important.”

Rachel: “To me, what’s important is that our managers appreciate the value of objective, nonbiased information. And that they use that information to make this company more effective. Do you see how important that is?”

Jack: “Well, if you put it that way.”

Rachel: “Let’s agree that three of us will meet here one week from today. Jack, you’ll discuss with all three call center supervisors what new features they think are needed. Linda, you’ll talk to at least three of our major customers and find out what they think. And let’s take it from there. Any questions?”

Summary

To communicate productively, a group has to be able to challenge its members’ assumptions. The most important assumptions to examine are always the ones that people cling to most dearly. Often these assumptions are based on deeply held beliefs. Unmasking these beliefs and assumptions helps us learn and understand what motivates us – and raise the level of the group discussion and decision-making.

From a management perspective, this is a skill we need to model ourselves before we can ask it of others. By inviting other people to test our assumptions, we set an example we can then use in our communications with them.

Note: People who want to learn more about the Circle of Assumptions may want to purchase a copy of the book “Straight Talk: Turning Communication Upside Down for Strategic Results at Work.”

Client Member Area

Client Member Area