Background:

- Major public broadcasting company.

- Producer of highly acclaimed public television shows.

- Besieged by competition and reductions in federal and corporate funding.

Key Challenges:

- Losses in two of the last three fiscal years.

- Downward trend in membership.

- Lack of internal consensus about the financial viability of key department.

- New competitors, including internet and cable.

- Competition from local stations.

Solution:

- Build and grow a strong membership base by refining programming to focus on target demographic.

- Re-position production for long-term growth.

- Maximize revenue potential from key programs.

Meaningful Change in a Short Timeframe

The Chief Operating Officer was committed to getting to the heart of performance issues that were causing the organization to stumble. He also knew that his position made it difficult to be objective. Late in the year – with the clock ticking down to the start of budgeting for the next two fiscal years – he called Leading Resources Inc. (LRI).

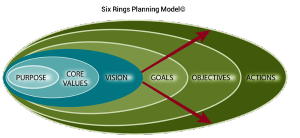

During an intensive three-month “pit stop,” LRI president Eric Douglas guided a dozen of top managers through a process that resulted in a focused set of goals and objectives leading to sustainable growth in the long term and operating surpluses in the short term.

“Experience has taught me it’s valuable to bring in a third party, someone who is absolutely agnostic as to personalities and biases,” the CEO said.

He had collaborated with Douglas when the CEO served as Chief Financial Officer at KQED, San Francisco’s public television station, and was impressed by his insightful, no-nonsense style, as well as his experience working in the media industry.

“I was impressed by Eric’s knowledge of the media business,” said the Chief Executive Officer. “He’s smart and very direct. He had the respect of the staff from the beginning.”

Step 1: The Situation Analysis: Identifying Which Opportunities to Focus On

The first step for Douglas is to gain insight into what is happening. In confidential interviews with managers, he asked frank questions: What’s causing the current situation? What conflicts underlie these issues? Why can’t the organization address them? What factors need to be in place to achieve success?

“The key business driver was revenue from its members,” Douglas said. “However, the programming and membership departments were operating as silos.”

Douglas found that neither department had a clear picture of the target audience they were trying to attract. “It seemed to me that the opportunity lay in building a tighter value chain between viewers and members,” Douglas said.

After a week of interviews, Douglas prepared a situation analysis, focusing on what he felt were the two most crucial opportunities to address during the strategic planning process.

- Strengthen and grow membership through targeted programming. Outside of pledge periods, programming decisions were often made using a loose definition of “public service” and “quality.” Douglas recommended that Programming and Membership departments work closely together to define the demographics of their target audience. As the two departments fine-tuned programming to reach this target audience, Gross Ratings Points (GRPs) – an industry measurement of time spent viewing – would guide them.

- Restructure production operation for long-term profitability. Producing had become less economically viable for most major public television stations. With competition falling away, we had the potential to turn its production operation into a long-term growth engine. But only if managers could impose the discipline it would take to restructure their Production Portfolio to favor profitability.

Step 2: Creating Task Forces

Early in the process, the management team met for the first of three strategy sessions. Douglas kicked off the meeting by presenting his analysis.

“People are always relieved when they see the organization laid out, warts and all, so they can talk about it.” Douglas said. “The biggest surprise for many people was that there was a lot of agreement around the weaknesses of the station.”

Douglas assembled the team into task forces to address the opportunities identified in his analysis. Each task force brought together people from multiple departments to collaborate on a specific set of assignments. “Eric’s manner encourages people to express their points of view about issues,” the CEO said. “At the same time, he’s no-nonsense. He keeps the process moving forward. He doesn’t allow the discussion to get into circular arguments that lead nowhere.”

Step 3: Developing Productive “Learning Loops”

“Some of us were surprised by how little we actually understood the financial and operational underpinnings of everything we do,” said the Head of Production. “There was some confusion over resource impacts, margins and so forth. It was the beginning of a process to get that clarity.”

Douglas calls this building “learning loops.” “As decision-makers share information across departments, their ability to make better decisions rises,” he says.

Douglas sees his role as both a catalyst and a devil’s advocate. “I have taken part in strategic planning processes that failed because the consultant was ‘facilitating’ discussions people wanted to have, rather than telling us which discussions we should be having,” he said. “I ask tough questions and make sure people spend time asking themselves tough questions. Sometimes it is painful. But having an honest dialogue about areas of conflict is the only way to break down barriers and find more creative resolutions.”

Bruns agrees. “When he needs to, Eric he can be firm with everyone at any level of the organization,” he said. “Sometimes it’s easier to be firm with people higher up in the organization than with people working in the ranks. You don’t want to appear heavy-handed. Eric is able to do it in a way that’s very constructive.”

Step 4: Moving from Breakthrough to Strategy

In some cases, the road to consensus proved a bit bumpy. Here’s a brief recap of what transpired over 12 weeks.

Membership and Programming

While the viewing audience was declining, two core groups remained strong and ripe for growth: children and educated women 50+.

Initial Insights: The Membership and Programming Task Force expanded their target audience to include men and women 45+. Guided by results of a major industry study correlating a rise in GRPs with increased multiyear memberships, the group tackled its first task: determining how well their prime-time line-up – a random mix of standard PBS fare – fit its target audience.

Hurdles: There was a lot of room for improvement. But first, we had to clear a major hurdle: the fear of offending PBS by shopping for programming elsewhere. PBS underwrites many productions – an area this organization is keen to develop into a long-term profit center.

Breakthrough Decision: the management team decided its first priority was to increase GRPs – which meant dropping or moving PBS shows that its target audience wasn’t watching.

New Strategy: Using GRPs as a yardstick of success focused their Membership and Programming departments on the importance of collaborating to increase membership dues and renewal rates. The departments meet regularly to analyze the latest GRPs and identify new areas of opportunity based on feedback from viewers.

Production

“It’s very hard to say no in public television,” admitted the CEO. As a result, there was no litmus test for the profit potential of projects production department decided to take on.

Initial Insights: The management team believed that “production was in our organization’s DNA.” “Yet, privately several people wondered whether we could continue in production,” Douglas said.

Hurdles: Douglas led the group through various scenarios – including exiting the production business altogether. “It was a painful discussion,” he said. “But we had to look that scenario in the eye and investigate whether, strategically, it made the most sense.”

Breakthrough Decision: “The beauty of having the conversation about getting out of production was that it scared people. It made them realize that production was not a sacred cow. They decided to purposefully create a future with production, but to be a lot more steely about the projects they undertake,” Douglas said.

New Strategy: In addition to nurturing its core portfolio of successful local and national programs, we adopted a more rigorous framework for accepting production projects. “I’ve officially terminated four projects,” the CEO reported. “Having a business framework gives us a basis for being more discriminating in our choices.” This sets the stage for production to become a growth engine.

Moving Ahead with Measurable Performance Goals

Moving ahead with a clearly defined set of performance goals for the next two fiscal years, they are focused on:

- Increasing GRPs by 6% in the target demographic.

- Increasing net membership revenues by 5%.

- Reducing margins from production by 10%.

“I would encourage any CEO to go through this process,” the CEO said. “In a very short time, we were able to clarify our expectations and unify the staff around common goals, which are the foundation of our new budget. Now, we have a consensus about the next steps we need to take and performance metrics that will let us know when we reach our goals. We’ve really moved forward as an organization.”

“I came away with a certain optimism that we can achieve the goals we want to achieve,” Bruns said. “While the problems we’re facing over the next years are difficult, they’re not insurmountable. This is my second experience with Eric and I wouldn’t hesitate to call on him again. I have that much confidence in him.”

Read more Case Studies or view Examples of Client Experiences.

We hope you enjoyed this strategic planning case study. Learn more about our strategic planning approach, or to schedule a meeting with LRI, contact us online.

Client Member Area

Client Member Area