Watching executives from British Petroleum, Transocean and Halliburton testify before Congress about the Gulf oil spill on Tuesday reminded me of the cardinal rules of leading through a crisis. Unfortunately, it looks like the BP-TO-HB trio never got the memo.

There are two rules to follow in a crisis. Rule number one is this: Protect other people first – customers, employees and citizens. Not your shareholders or yourself. Protect the public and your customers, and the shareholders will follow. Why? Because the long-term reputation and goodwill of your organization are more important than any short-term risk to shareholder value or your own job security.

Rule number two is a corollary to the first: Be prepared to reframe and expand your level of responsibility. In other words, accept responsibility even if you’re not at fault. This may feel counter-intuitive, especially when someone else is clearly culpable. But reframing and expanding your level of responsibility will help lead you out of the crisis.

Consider the Exxon Valdez disaster. When it went aground in Alaska’s Prince William Sound in 1989, eleven million of oils spilled onto pristine shoreline. In the immediate aftermath, Exxon’s CEO Lawrence Rawl was slow to accept responsibility. Instead he issued a flurry of press releases stating that the company was investigating the accident. The opportunity to quickly contain the spill was squandered. Hundreds of miles of coastline were fouled.

Public furor built and the company’s reputation plunged. Several weeks passed before Rawl grudgingly announced that the company would take responsibility for the clean up. Eventually, thousands of workers and volunteers were mobilized to mop up the oil, save the wildlife, and minimize the damage to the extent possible. But Exxon’s public image was left in tatters because its immediate response was too slow. William Reilly, then head of the Environmental Protection Agency, said Rawl’s response was “a casebook example of how not to communicate to the public when your company messes up.” Rawl’s reputation never recovered.

In contrast, when a container of Odwalla apple juice contaminated by the bacteria e coli resulted in the death of a child in 1996, CEO Greg Stepensall stepped in right away and assumed personal responsibility. He recalled every Odwalla product. He paid out huge sums to the families affected by the tainted products. He held regular press conferences to ensure the public knew what was going on and how the company was responding. For more than a year, Odwalla retooled its production lines, adding flash pasteurization to ensure no future incidents could occur. Sales fell 90 percent but Odwalla survived with its reputation intact.

As the Exxon Valdez and Odwalla examples show, leaders have a clear choice in how they frame their response to a crisis. On the one hand, they can respond out of a “protect ourselves” mentality. Or leaders can think and act out of a larger ethical context, as Odwalla did.

The Tylenol scare in 1986 is another case in point. It was clear when cyanide-laced containers of Tylenol were found on supermarket shelves that a pathological killer was responsible. Johnson & Johnson’s executives could have focused on the criminal aspects and exhorted police to take responsibility for catching the perpetrator. (Indeed, he was caught within a matter of days.)

But Johnson & Johnson’s executives understood the need to immediately take responsibility for the safety of their consumers. This led the company to recall every Tylenol product, design strong anti-tampering packaging, and conduct a massive awareness-building campaign. It is estimated to have cost the company $2 billion, but Johnson & Johnson emerged the stronger for it.

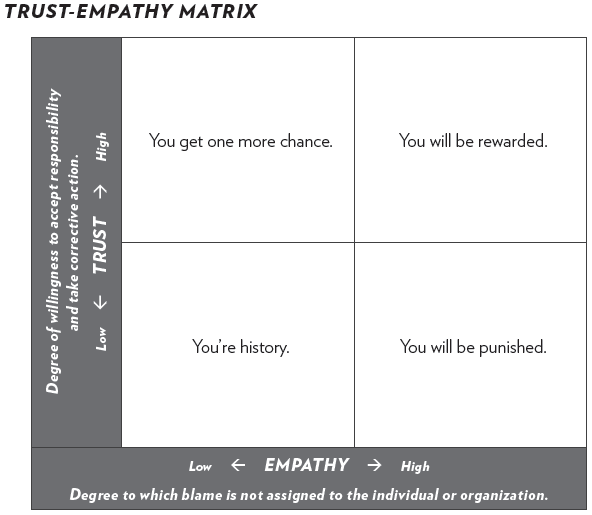

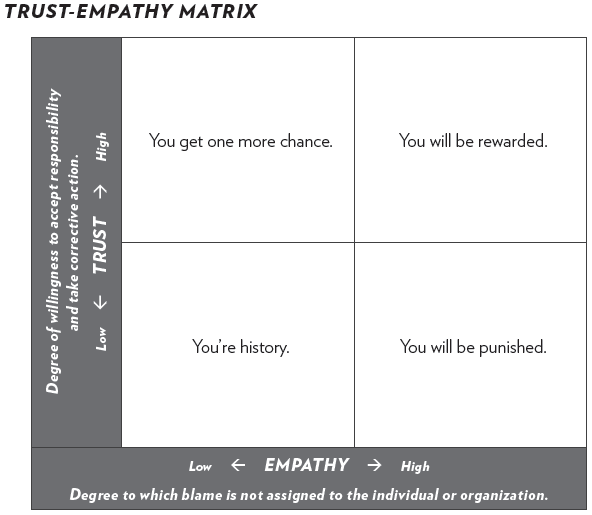

The bottom line is this: When a crisis hits, two dynamics take over: Trust and Empathy.

The empathy scale is governed largely by facts outside your control. In the case of the Exxon Valdez tanker spill, there was little question that the captain was drunk and that Exxon, as his employer, was at fault. Exxon’s leaders had little control over the empathy scale. But they did have control over the trust scale, which they messed up. In the Tylenol case, Johnson & Johnson was clearly not at fault. Yet it chose to assume full responsibility. As a consequence, the company was rewarded.

In Japanese corporate cultures, managers are trained to accept personal responsibility for anything that goes wrong on their watch. To Western eyes, this seems odd. We’re amazed when a Japanese CEO resigns because of the incorrect action of a freighter captain or an accounting irregularity. Yet as the Trust/Empathy Matrix shows, it’s also smart business. When a crisis hits, assuming responsibility and taking immediate, corrective action is more important than safeguarding your job.

Too bad the folks at British Petroleum, Transocean and Halliburton haven’t learned that lesson.

LRI’s consulting is designed to achieve real, meaningful change for our clients.

Client Member Area

Client Member Area