Public Utility Governance

Board Governance Case Study One area of consulting that our firm specializes in is governance, specifically Board governance for large public agencies. The work we’ve done in this area has been groundbreaking – resulting in much clearer definitions of what the Board does and doesn’t do and stronger alignment around strategic goals and performance expectations. This work has proven successful for a number of public agencies in the United States. The purpose of this case study is to describe this work in some detail.

At its heart, governance simply means how decisions are made. It requires clarifying the decision-making roles and responsibilities of each layer of the organization, starting with the Board of Directors. Our work in this area has focused on public utility companies that provide electricity, water, gas, or wastewater treatment, where the Board is elected by the ratepayers of a defined district.

Public utilities are far different from investor-owned utilities, such as PG&E, which are owned by shareholders and where governance is controlled by an internal, non-elected board of directors. In these utilities, regulators try to ensure that the utility Board will work in the best interest of its customers, but ultimately it is profit rather than public service that guides its decision making. The role of a public utility Board is typically defined in state or federal statute, sometimes complemented by bylaws or governing documents that further define the Board’s role. But the actual manner in which the Board governs is often left undefined.

Our work on governance for a large public utility began with a call in 2001 from Peter Keat, the president of the Board of Directors of the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD). Peter was familiar with our firm through our work with another client. Peter told me that the SMUD Board needed help figuring out its role in governing the utility. I told Peter that I thought we could help – and proposed that we start by getting a clear sense of the current situation.

Let me pause here and describe our firm. LRI’s purpose is developing leaders and leading organizations. We do it by facilitating change – by providing a clear assessment of the current state, facilitating decisions about whether change is needed, and helping to determine what exactly change is needed and how to make it happen.

We entered into a contract with SMUD to do a situation assessment, and in 2002 a two-person team from our firm began a series of interviews. We talked to all seven Board members. We talked to the General Manager. We talked to other leaders within SMUD. From Board members, we learned that while the utility was working well, they felt the Board’s role was very unclear. They felt Board members were exercising no leadership and simply “rubber stamping” the General Manager’s recommendations and decisions. We’re wasting our time, one member said, approving lots of contracts; instead we need to actually set strategic goals and hold the GM accountable for achieving them.

From the General Manager we learned she felt she had seven bosses who weren’t aligned in what they wanted SMUD to accomplish or even in how to run it. Her direct reports, the company’s senior managers, told us that individual Board members were making end runs around the General Manager, telling managers how to run specific programs. We heard frustration and anger that the utility wasn’t being more effectively governed. Everyone seemed to think the status quo was not acceptable – but there was no clear consensus on what changes needed to occur.

We also talked to leaders of other public utilities. In Colorado we found an example of a municipal utility that was operating well because the mayor and city council had defined a clear set of performance expectations. Several people talked to us about different governance models, including John Carver’s “policy governance” model. One of the SMUD Board members had invited Carver to speak to the SMUD Board. Carver spoke to the Board in person, and while a couple of Board members found his model intriguing, they found Carver himself to be somewhat off-putting, telling the Board that his system was the only “correct” form.

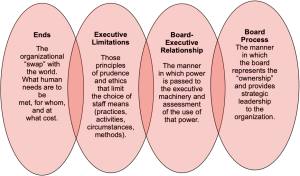

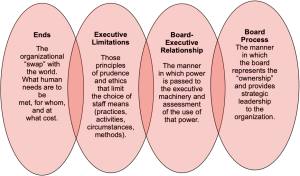

A quick note about the “Carver model.” Carver says that Boards need to develop four buckets of written Board policy, as the diagram below shows. Carver maintains that all four buckets are important – that the system doesn’t work otherwise.

When we talked to SMUD’s General Manager about Carver’s model, she said she appreciated certain aspects of it. But, she said, there were certain aspects she did not appreciate. She was savvy in understanding that one of the buckets, the executive limitations, could set her up for what she called “gotcha” moments, where she would be held accountable for things beyond her control. She said she could imagine how the other three buckets might be helpful, so long as the executive limitations were off the table. Several Board members told us they were aware of her opposition to Carver’s model and could not support it for that reason.

In the spring of 2002, our team completed the situation assessment, wrote up the findings, and brought those findings to a public meeting of the SMUD Board. The General Manager was also there along with her senior management team. Here’s what we presented:

- The Board felt the General Manager and staff were doing a fine job running the utility.

- The Board members were unclear about their role and wanted the Board’s role to be better defined.

- Board members wanted to use their time and skills more effectively.

- Board members wanted to get away from approving so many contracts and instead focus on strategic issues.

- Board members wanted to have real policy discussions in which differences could surface and be debated in a healthy way.

- Most Board members thought the status quo was unacceptable and that something needed to change.

- While some Board members were intrigued by Carver’s model, they did not want to adopt that approach.

- The GM supported the Board’s desire to clarify its role, but she did not support adopting Carver’s approach.

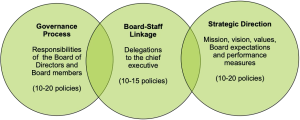

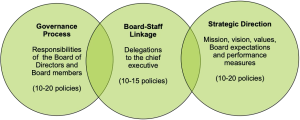

Our recommendation was that the Board develop a policy governance framework but not strictly follow Carver’s model. We proposed dropping the executive limitations and amplifying the “ends” policies to be more explicit about the results that the utility district was to achieve. We suggested calling these “strategic directive” policies. In short, we proposed that the Board develop three buckets of policies, rather than four, as show below:

After presenting these findings, we asked people what they thought. Several Board members voiced support for our conclusions – and thought we should enter into a new phase of work to facilitate the development of this governance framework. A few expressed reservations, saying they were uncertain whether anything would change. The General Manager said she supported the direction we recommended and said she would actively help in any way she could. Bolstered by her support, the Board agreed to embark on a new phase of work. Specifically, we would begin by developing written policies that defined the purpose of the Board and its roles and responsibilities (the Governance Process policies).

And so our team began facilitating discussions with the Board. We drafted a few initial policies defining the purpose of the Board (whom it serves, what it does at a high level) and the governance focus of the Board (what specific activities it should engage in – and what it should not do). We had no other model to go on, other than some examples from Carver’s book and our own sense of what were important topics to cover. Over the initial months of our engagement we met several times with the Board and facilitated discussions about the draft policy language. Ultimately we came up with the following Governance Process (GP) policies:

GP-1: The purpose of the Board

GP-2: The governance focus of the Board

GP-3: The Board’s job description

GP-4: The Board’s work plan and agenda planning

GP-5: Election of Board president and vice president

GP-6: Role of the Board president

GP-7: Guidelines for Board member behavior

GP-8: Board committee principles

GP-9: Board committee chairs

GP-10: Board training and orientation

The full Board discussed these drafts, made refinements, and ultimately endorsed them. Our attention then turned to developing the Strategic Directive policies, detailing the results the Board expected the utility to achieve and how to measure those results. This took more time than the first two buckets of policy. The Board members and executive team got actively engaged in sharing and debating their priorities for SMUD. Some wanted to emphasize low rates, others focused on environmental sustainability, others on high levels of customer service. In some areas, like reliability and customer service, the measures of performance were relatively easy to figure out. But in others, like environmental leadership or economic development, it was not as easy. Ultimately, the Board came up with this set of Strategic Directive (SD) policies:

SD-1: Purpose and vision

SD-2: Competitive rates

SD-3: Access to credit markets

SD-4: Reliability

SD-5: Customer relations

SD-6: Safety

SD-7: Environmental leadership

SD-8: Employee relations

SD-9: Resource planning

SD-10: Innovation

SD-11: Public power business model

SD-12: Ethics

SD-13: Economic development

The last piece to get in place was the Board-Staff Linkage policies. These define the relationship between the Board and the General Manager and the specific delegations to the General Manager. Using the same approach, we drafted examples of these policies, shared them with a Board committee, and facilitated refinements. The General Manager and her senior team participated actively in all of these discussions and were key in helping to draft the specific delegation language.

Ultimately, we drafted the following Board-Staff Linkage (BL) policies:

BL-1: Board-General Manager relationship

BL-2: Board-General Counsel relationship

BL-3: Board-Internal Auditor relationship

BL-4: Board-Special Assistant relationship

BL-5: Unity of Control

BL-6:Evaluating the General Manager’s performance

BL-7: Delegation to the General Manager

BL-8: Delegation with respect to procurement

BL-9: Delegation with respect to legislation and regulation

BL-10: Delegation with respect to real and person property

BL-11: Delegation with respect to claims and litigation

BL-12: Delegation with respect to power-related transactions

In 2003, the SMUD Board voted to adopt its new policy governance system. The Board then asked our team to help develop the regular process of monitoring each of the policies. We needed to figure out the calendar and schedule. And we needed to figure out how each policy would be monitored: What data would be collected and presented to the Board so that it could determine the level of compliance with each policy?

For the Governance Process policies, we decided that the ten policies should be monitored on a staggered basis over the course of a year. Each month a survey went out to Board members and executive team members to ask whether the Board was in compliance with a specific GP policy. The survey results were compiled and then brought to a Board committee for discussion and reflection. In this way, the Board got specific feedback about its performance.

A similar cadence was put in place to monitor the Strategic Directives. Each month, the General Manager and executive team put together a presentation to show the degree to which each SD policy was being met. For the strategic directive on reliability, for example, the executive team presented data about the frequency and duration of energy outages and the degree of uptime for every circuit.

For the Board-Staff Linkage policies, we decided on a blended approach. Some required a survey of Board members and executive team members (unity of control policy was one example). Others required the General Manager or her designees to gather evidence to show compliance (e.g. the delegation policies).

And so we began a regular cadence of monitoring the different policies. The Board also began the process of refining the policies as they realized that the words really mattered, that the words needed to precisely convey their governing intention and direction. A few of the policies, notably customer relations and environmental leadership, were revised three times in the first few years that the system took hold.

The diagram below shows the full cycle of policy setting, policy monitoring, and policy refinement.

Board members also realized that if they wanted something new to get done, they would have to draft policy language and build consensus for it. One Board member, for example, wanted more of the utility’s power lines to be laid underground, especially in key commercial corridors. So we worked with an ad hoc committee of the Board to draft language. We facilitated several iterations before the language was acceptable to a majority of Board members and the General Manager. The result was SD-14, the “system enhancement” policy, which was approved and incorporated into the policy framework in 2005.

As the new governance system took hold, the General Manager began to speak publicly about its advantages. One benefit of the new governance system, she said, was that no individual Board member could direct the staff any longer. The entire Board directed the utility through written policies. Another benefit was stability: By putting the Board’s expectations into writing, it created a clear, stable set of performance expectations that the utility could use to guide its operations and it long-term planning. For an organization that needed to make large capital investments, the policy governance system meant they could eliminate the guesswork around what direction the Board wanted to take.

The third benefit, she said, was the increased alignment across the organization. Everyone from front-line employees to the executive team understood the Board’s role in setting strategic direction and – because the policies were shared publicly – understood what results the Board wanted the utility to achieve.

As part of our ongoing work with the SMUD Board, we also began conducting an annual holistic survey of the Board members and executive team about how they felt the new governance system was working. We developed a 35-question survey that looked at all aspects of governance, from the clarity of roles and responsibilities to the quality of decision making, to the quality of the communication between the Board and General Manager.

In analyzing the results, we noticed several interesting trends. First, when we initially did the survey prior to the completion of the policy governance framework, the scores were abysmally low, especially in the clarity of roles and responsibilities and in the level of trust and communication between the Board and the General Manager.

As the policy governance system took effect, we saw the scores rise significantly in all categories. For example, on the question of clarity of decision-making roles, that score skyrocketed. Scores for trust between the Board and General Manager also rose. Perceptions of the effectiveness of the Board increased. This survey continues to be conducted annually. And the Board uses the results to decide whether to make any refinements to enhance the effectiveness of the governance framework.

This new “strategic policy governance” model, as we called it, attracted notice from other organizations. One was a state agency in California where we successfully introduced and developed the same framework. Another was the public utility in Omaha, Nebraska, which noticed what SMUD was doing and wanted to try to replicate it. Next came Tacoma, Washington, and then Long Island. The goals and dynamics were different in each place, but we learned that we could customize and adapt the framework to provide a sturdy and sound way for the Board to lead the organization. To date, we have helped eight public agencies adopt the model.

In conclusion, there are reasons why this approach to Board governance has worked so well and why we think it is ground-breaking:

- First, the system bakes in the principle of unity of control. It is the Board, and not board members, that directs the organization.

- Second, the Board directs the organization through clear, written policies, not some other means. This provides clarity to the General Manager and managers – and provides clarity and transparency to the public.

- Third, the ongoing monitoring process continually raises awareness among new and veteran Board members and the General Manager and managers about the things that the Board has said are important to it, both in defining its own responsibilities, as well as in the delegations and strategic directives.

- Fourth, the monitoring process provides a way for the organization to measure how well it is doing on a regular basis, and in an open and transparent way.

- Lastly, the system builds alignment across the organization, from the Board to front-line employees, about the things that are important and how performance will be measured, which brings a level of focus and accountability often not seen in public agencies.

It’s been exciting to see how a systemic approach to governance can bring about such profound changes. And it is nice to think that it is a lasting form of governance, one that endures even as the people responsible for it change.

Client Member Area

Client Member Area