The role of a leader often boils down to solving complex problems. People have a natural tendency to want to solve problems in ways that are comfortable for them. In some cases, this can be detrimental, if a leader picks only problems that can be quickly resolved, or doesn’t take the time to identify the root problem. In my experience, people can become more comfortable solving tough problems if they have a series of proven steps to help them.

1. Define the problem.

1. Define the problem.Take an initial stab at defining the problem in a way that identifies the harm that is occurring. For example, “we aren’t being effective in converting online inquiries into sales, resulting in a loss of revenue.”

Put numbers to the problem. How many inquiries in a given month? What are the potential losses in sales? How is this trending?

Here’s your opportunity to generate options. What if you dedicated one sales person full time to following up on online inquiries? What if it was a bigger team? What if you contracted with another company to service them?

It’s important to understand what criteria you will use to make to weigh different options. In this case, financial benefit and cost are the obvious criteria. Less obvious criteria might be the degree to which servicing these inquiries is mission critical – or might prove disruptive to other goals.

Using your evidence and criteria, build a case for each alternative. Try to keep it to 2-4 alternatives. Looking down the road a year, what might be the expected results? The unintended consequences?

All tough decisions involve tradeoffs. Look at your projected outcomes and ask: What would be the upside and downside of each. The hidden costs. Who might be the losers? In this case, you might see that hiring a new sales team to service the online inquiries would have a hidden benefit in building a more robust online presence for your company. But it would also cause friction with the sales managers in your various territories.

Ultimately, you need to make a call. Sometimes, it’s clear what you need to do. Sometimes you need to confer further, reiterate your problem definition, and go through the process again. And sometimes you need to simply decide the status quo is fine.

To be persuasive in making your case, you need to tell the story about how you got there, how you weighed the pros and cons, how you projected the outcomes, and how you analyzed the tradeoffs. There will always be multiple scenarios and multiple perspectives. So don’t worry so much about whether you found the right decision. Be willing to show your struggle with the problem. And why you got to your particular solution.

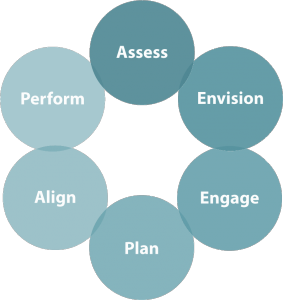

LRI designs and facilitates planning processes to help organizations improve their business effectiveness and efficiency: https://leading-resources.com/consulting/processimprovement/